There is no doubt that the Taliban currently have the initiative in Afghanistan, but the movement has a long way to go before it can effect a decisive victory. While the Taliban need not evolve from insurgent group to conventional army to achieve that goal, they must move beyond guerrilla tactics, consolidate their disparate parts and find ways to function as a more coordinated fighting force.

Analysis

The United States is losing in Afghanistan because it is not winning. The Taliban are winning in Afghanistan because they are not losing. This is the reality of insurgent warfare. A local insurgent is more invested in the struggle and is working on a much longer time line than an occupying foreign soldier. Every year that U.S. and NATO commanders do not show progress in Afghanistan, the investment of lives and resources becomes harder to justify at home. Public support erodes. Even without more pressing concerns elsewhere, democracies tend to have short attention spans.

At the present time, defense budgets across the developed world — like national coffers in general — are feeling the pinch of the global financial crisis. Meanwhile, the resurgence of Russia’s power and influence along its periphery continues apace. The state of the current U.S.-NATO Afghanistan campaign is not simply a matter of eroding public opinion, but also of immense opportunity costs due to mounting economic and geopolitical challenges elsewhere.

This reality plays into the hands of the insurgents. In any guerrilla struggle, the local populace is vulnerable to the violence and very sensitive to subtle shifts in power at the local level. As long as the foreign occupier’s resolve continues to erode (as it almost inevitably does) or is made to appear to erode (by the insurgents), the insurgents maintain the upper hand. If the occupying power is perceived as a temporary reality for the local populace and the insurgents are an enduring reality, then the incentive for the locals — at the very least — is to not oppose the insurgents directly enough to incur their wrath when the occupying power leaves. For those who seek to benefit from the largesse and status that cooperation with the occupying power can provide, the enduring fear is the departure of that power before a decisive victory can be made against the insurgents — or before adequate security can be provided by an indigenous government army.

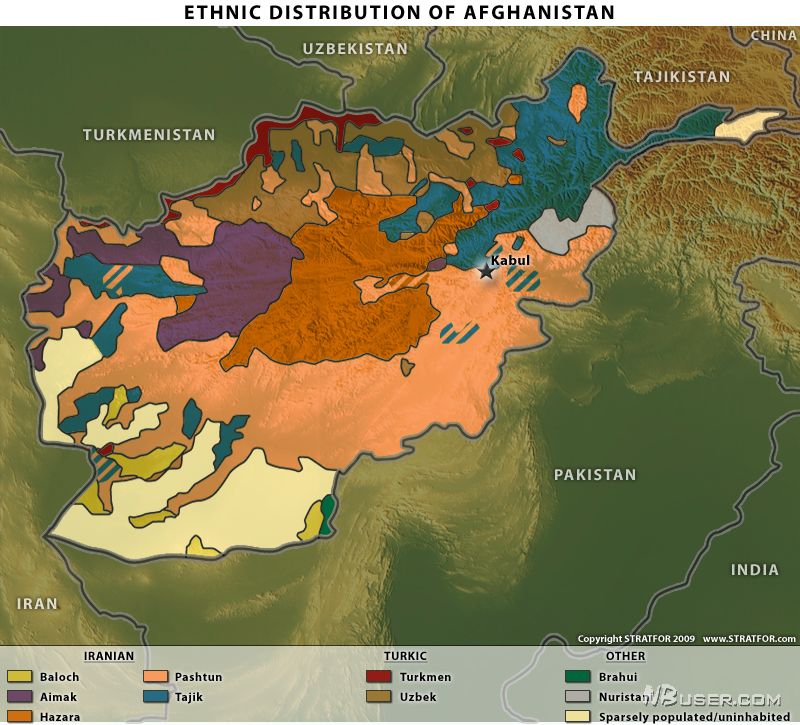

Let us apply this dynamic to the current situation in Afghanistan. In much of the extremely rugged, rural and sparsely populated country, a sustained presence by the U.S.-NATO and the Taliban alike is not possible. No one is in clear control in most parts of the country. The strength of the tribal power structure was systematically undermined by the communists long before the actual Soviet invasion at the end of 1979. The power structure that remains is nowhere near as strong or as uniform as, say, that of the Sunni tribes in Anbar province in Iraq (one important reason why replicating the Iraq counterinsurgency in Afghanistan is not possible). Indeed, it is difficult to overstate the unique complexity of the ethnic, linguistic and tribal disparities in Afghanistan.

The challenge for each side in the current Afghan war is to become more of a sustained presence than the other. “Holding” territory is not possible in the traditional sense, with so few troops and hard-line insurgent fighters involved, so a village can be “pro-NATO” one day and “pro-Taliban” the next, depending on who happens to be moving through the area. But even village and tribal leaders who do work with the West are extremely hesitant to burn any bridges with the Taliban, lest U.S.-NATO forces withdraw before defeating the insurgents and before developing a sufficient replacement force of Afghan nationals.

Today, the two primary sources of power in Afghanistan are the gun and the Koran — brute force and religious credibility. The Taliban purport to base their power on both, while the United States and NATO are often derided for wielding only the former — and clumsily at that. Many Afghans believe that too many innocent civilians have been killed in too many indiscriminate airstrikes.

So it comes as little surprise that popular support for the Taliban is on the rise in more and more parts of Afghanistan, and that this support is becoming increasingly entrenched. For years, U.S. attention has been distracted and military power absorbed in Iraq. Meanwhile, a limited U.S.-NATO presence and a lack of opposition in Afghanistan have allowed various elements of the Taliban to make significant inroads. This resurgence is also due to clandestine support from Pakistan’s army and Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) directorate, as well as proximity to the mountainous and lawless Pakistani border area, which serves as a Taliban sanctuary.

But the Taliban still have not coalesced to the point where they can eject U.S. or NATO forces from Afghanistan. Far from a monolithic movement, the term “Taliban” encompasses everything from the old hard-liners of the pre-9/11 Afghan regime to small groups that adopt the name as a “flag of convenience,” be they Islamists devoted to a local cause or criminals wanting to obscure their true objectives. Some Taliban elements in Pakistan are waging their own insurrection against Islamabad. (The multifaceted and often confusing character of the Taliban “movement” actually creates a layer of protection around it. The United States has admitted that it does not have the nuanced understanding of the Taliban’s composition needed to identify potential moderates who can be split off from the hard-liners.)

Any “revolutionary” or insurgent force usually has two enemies: the foreign occupying or indigenous government power it is trying to defeat, and other revolutionary entities with which it is competing. While making inroads against the former, the Taliban have not yet resolved the issue of the latter. It is not so much that various insurgent groups with distinctly different ideologies are in direct competition with each other; the problem for the Taliban, reflecting the rough reality that the country’s mountainous and rugged terrain imposes on its people, is the disparate nature of the movement itself.

In order to precipitate a U.S.-NATO withdrawal in the years ahead, the Taliban must do better in consolidating their power. No doubt they currently have the upper hand, but their strategic and tactical advantages will only go so far. They may be enough to prevent the United States and NATO from winning, but they will not accelerate the time line for a Taliban victory. To do this, the Taliban must move beyond current guerrilla tactics and find ways to function as a more coherent and coordinated fighting force.

The bottom line is that neither side in the struggle in Afghanistan is currently operating at its full potential.

To Grow an Insurgency

The main benefits of waging an insurgency usually boil down to the following: insurgents operate in squad- to platoon-sized elements, have light or nonexistent logistical tails, are largely able to live off the land or the local populace, can support themselves by seizing weapons and ammunition from weak local police and isolated outposts and can disperse and blend into the environment whenever they confront larger and more powerful conventional forces. In Afghanistan, the chief insurgent challenge is that reasonably well-defended U.S.-NATO positions have no problem fending off units of that size. In the evolution of an insurgency, we call this stage-one warfare, and Taliban operations by and large continue to be characterized as such.

In stage-two warfare, insurgents operate in larger formations — first independent companies of roughly 100 or so fighters, and later battalions of several hundred or more. Although still relatively small and flexible, these units require more in terms of logistics, especially as they begin to employ heavier, more supply-intensive weaponry like crew-served machine guns and mortars, and they are too large to simply disperse the moment contact with the enemy is made. The challenges include not only logistics but also battlefield communications (everything from bugles and whistles to cell phones and secure tactical radios) as the unit becomes too large for a single leader to manage or visually keep track of from one position.

In stage-three warfare, the insurgent force has become, for all practical purposes, a conventional army operating in regiments and divisions (units, say, consisting of 1,000 or more troops). These units are large enough to bring artillery to bear but must be able to provide a steady flow of ammunition. Forces of this size are an immense logistical challenge and, once massed, cannot quickly be dispersed, which makes them vulnerable to superior firepower.

The culmination of this evolution is exemplified by the battle of Dien Bien Phu in a highland valley in northwestern Vietnam in 1954. The Viet Minh, which began as a nationalist guerrilla group fighting the Japanese during World War II, massed multiple divisions and brought artillery to bear against a French military position considered impregnable. The battle lasted two months and saw the French position overrun. More than 2,000 French soldiers were killed, more than twice that many wounded and more than 10,000 captured. The devastating defeat was quickly followed by the French withdrawal from Indochina after an eight-year counterinsurgency.

The Taliban Today

In describing this progression from stage one to stage three, we are not necessarily suggesting that the Taliban will develop into a conventional force, or that a stage-three capability is necessary to win in Afghanistan. Not every insurgency that achieves victory does so by evolving into the kind of national-level conventional resistance made legendary by the Viet Minh.

Indeed, artillery was not necessary to expel the Soviet Red Army from Afghanistan in the 1980s; that force faced and failed to overcome many of the same challenges that have repelled invaders for centuries and confront the United States and NATO today. But in monitoring the progress of the Taliban as a fighting force, it is important to look beyond estimates of “controlled” territory to the way the Taliban fight, command, consolidate and organize disparate groups into a more coherent resistance.

The Taliban first rose to power in the aftermath of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and before 9/11. They were not the ones to kick out the Red Army, however. That was the mujahideen, with the support of Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and the United States. The Taliban emerged from the anarchy that followed the fall of Afghanistan’s communist government, also at the hands of the mujahideen, in 1992. In the intra-Islamist civil war that ensued, the Taliban were able to establish security in the southern part of the country, winning over a local Pashtun populace and assorted minorities that had grown weary of war.

This impressed Pakistan, which switched its support from the splintered mujahideen to the Taliban, which appeared to be on a roll. By 1996, the Taliban, also supported by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, were in power in Kabul. Then came 9/11. While the Taliban did, for a time, achieve a kind of stage-two status as a fighting force, they have never had the kind of superpower support the Viet Minh and North Vietnamese received from the Soviet Union during the French and American wars in Vietnam, or that the mujahideen received from the United States during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.

But elements of the Taliban continue to enjoy patronage from within the Pakistani army and intelligence apparatus, as well as continued funding from wealthy patrons in the Persian Gulf states. The Pakistani support underscores the most important of resources for an effective insurgency (or counterinsurgency): intelligence. With it, the Taliban can obtain accurate and actionable information on competing insurgent groups in order to build a wider and more concerted campaign. They can also identify targets, adjust tactics and exploit the weaknesses of opposing conventional forces. The Taliban openly tout their ties and support from within the Afghan security forces. (Indeed, a significant portion of the Taliban’s weapons and ammunition can be traced back to shipments that were made to the Afghan government and distributed to its police agencies and military units.)

Moreover, while external support of the Taliban may not be as impressive as the support the mujahideen enjoyed in the 1980s, the Karzai government in Afghanistan is far weaker than the communist regime in Kabul that the mujahideen took down. In addition, as a seven-party alliance with significant internal tensions, the mujahideen were even more disjointed than the Taliban. Indeed, the core Taliban today are much more homogeneous than the mujahideen were in the 1980s. The Taliban are the pre-eminent Pashtun power, and the Pashtuns are the single largest ethnic group in Afghanistan. In addition, the leadership of Taliban chief Mullah Omar is unchallenged — he has no equal who could hope to rise and meaningfully compete for control of the movement.

While the Taliban continue to exist squarely in stage-one combat, the movement is increasingly becoming the established, lasting reality for much of the country’s rural population. For ambitious warlords, joining the Taliban movement offers legitimacy and a local fiefdom with wider recognition. For the remainder of the population, the Taliban are increasingly perceived as the inescapable power that will govern when the United States and NATO begin to draw down.

On the other hand, the Taliban’s ability to earn the loyalty of disparate groups, coordinate their actions and command them effectively remains to be seen. Monitoring changes in the way the Taliban communicate — across the country and across the battlefield — will say much about their ability to bring power to bear in a coherent, coordinated and conclusive way.